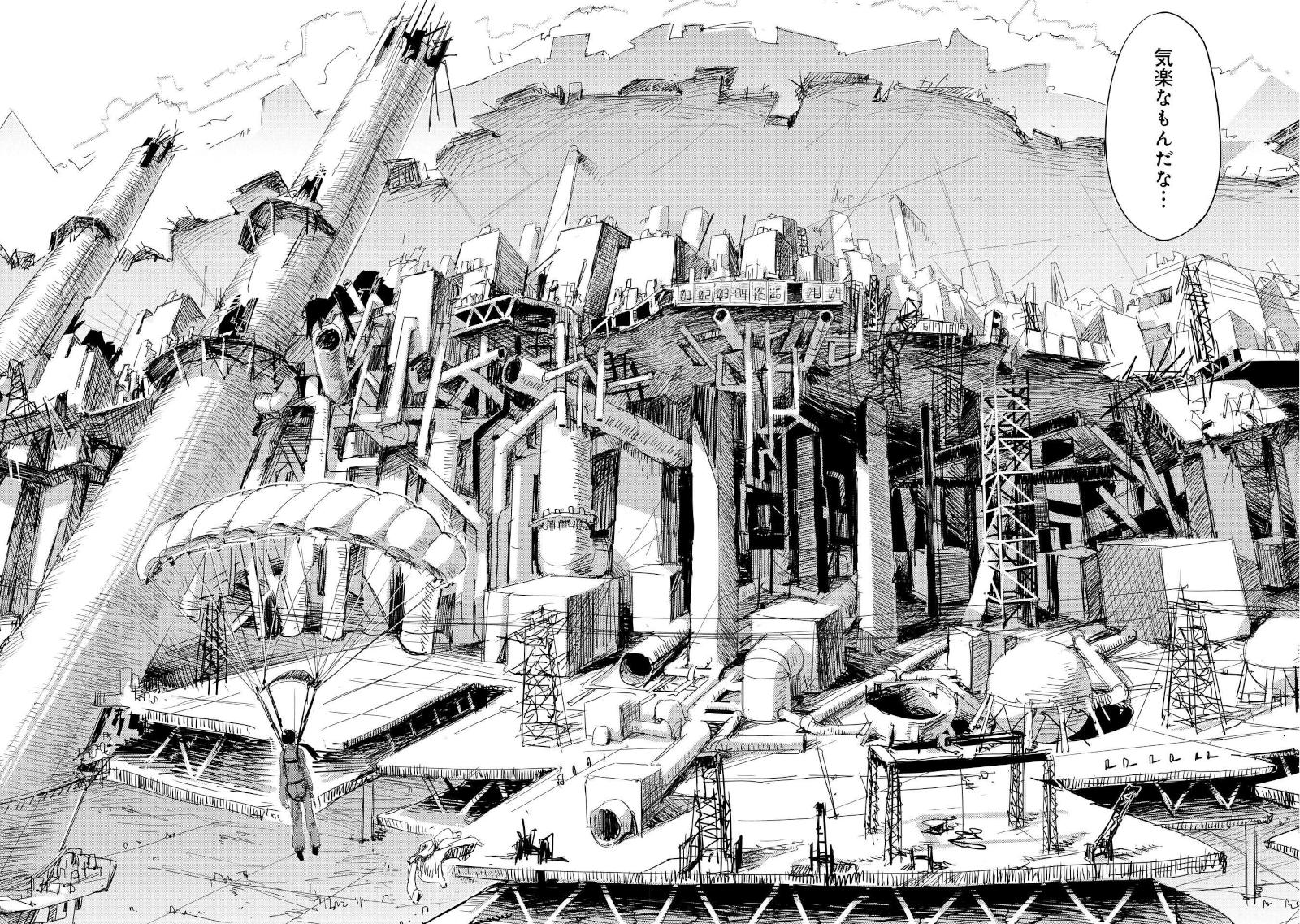

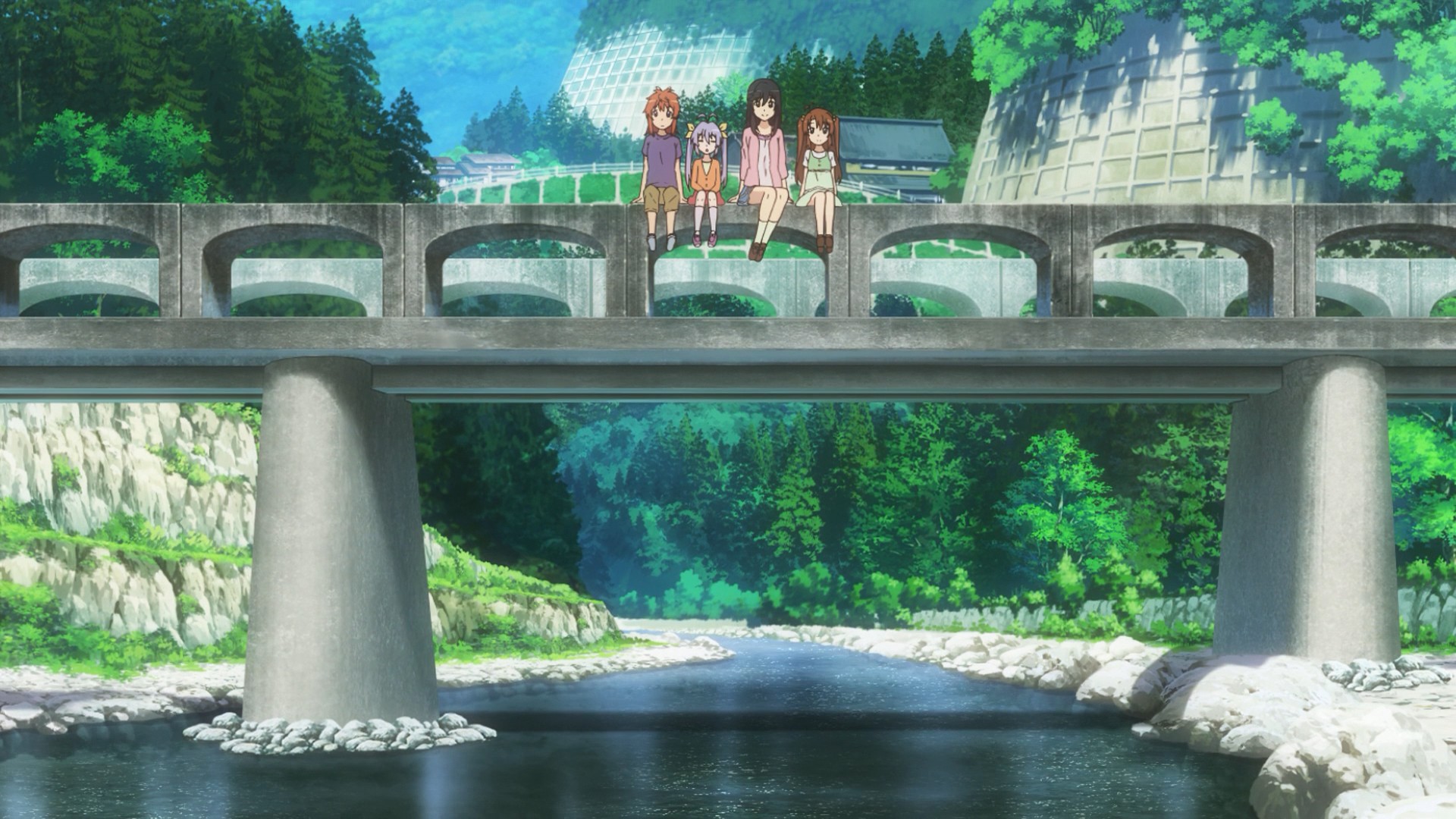

a long time ago, i read about an eye tracking study where the researchers found that while normal children will generally focus on characters in a tv scene, autistic children pay lots of attention to irrelevant stuff in the background. perhaps this is why i couldn't help but notice the rather excessive infrastructure in the background of this scene in the last episode of non non biyori repeat. then, trying to remember if there were any other examples, i also recalled that there was that whole escapade in the first season with crawling around drainage channels to get to a secret base in some sort of hulking concrete building of unclear utilization.

from my perspective, it just seems a bit odd because this is supposed to be the boonies, after all. there are some similarly treacherous (if not more), well-trafficked highways in my vicinity, and the way they usually deal with a cliff is by putting up one of those yellow road signs that says "rocks". as for water-related concrete structures, if you're out in the countryside you won't see any outside of a dam, and even those are for the most part made of dirt or big rocks instead of straight concrete.

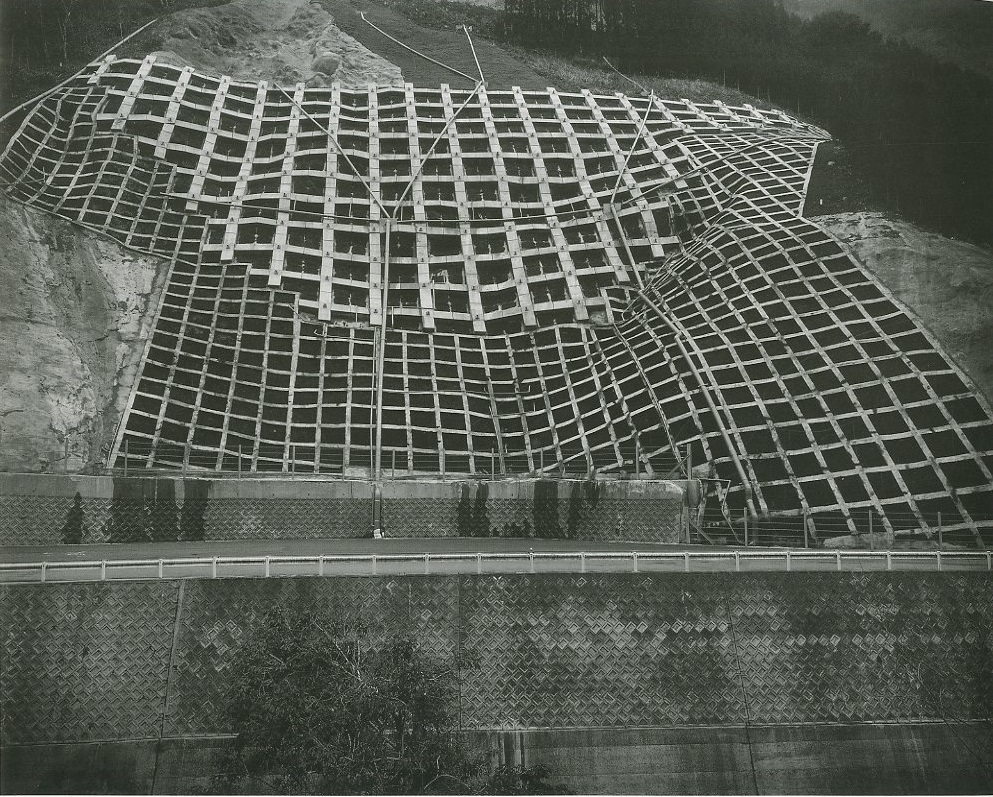

but anyone familiar with the japanese boonies (guilty) will know this isn't just a weird one-off anime thing, it's in fact quite representative. the japanese countryside really is filled with far more concrete infrastructure stuff than pretty much every developed country. what is the deal with that? in another case of all-too-familiar japanese exceptionalism, are japanese mountains just that much more crumbly and japanese waterways just that much floody? or perhaps the japanese are once again years ahead of everyone, able to defend their roadways from the falling rocks that clobber thousands in backwards countries? or maybe, something a lot more ominous is going on...

with these questions stewing in the back of my mind, i somehow serendipitously stumbled upon a book on exactly this topic, alex kerr's dogs and demons, subtitled "tales from the dark side of japan". yup, that means that unfortunately this is not going to end up being another pretty story about how advanced or safe or developed or enlightened japan is compared to western countries...

everyone knows how much nature is cherished in traditional japanese culture. could you even imagine haiku, screen prints, gardening, ikebana flower arranging, and japanese architecture without it? it even takes on a spiritual dimension in the form of japan's homegrown religion, shinto, which is based around reverence for nation as the dwelling place of gods. consequently, wikipedia directly describes shinto as a "nature religion". this is why it's so perplexing when you actually go out into said japanese nature after hearing all that and find... it's all been covered in concrete?

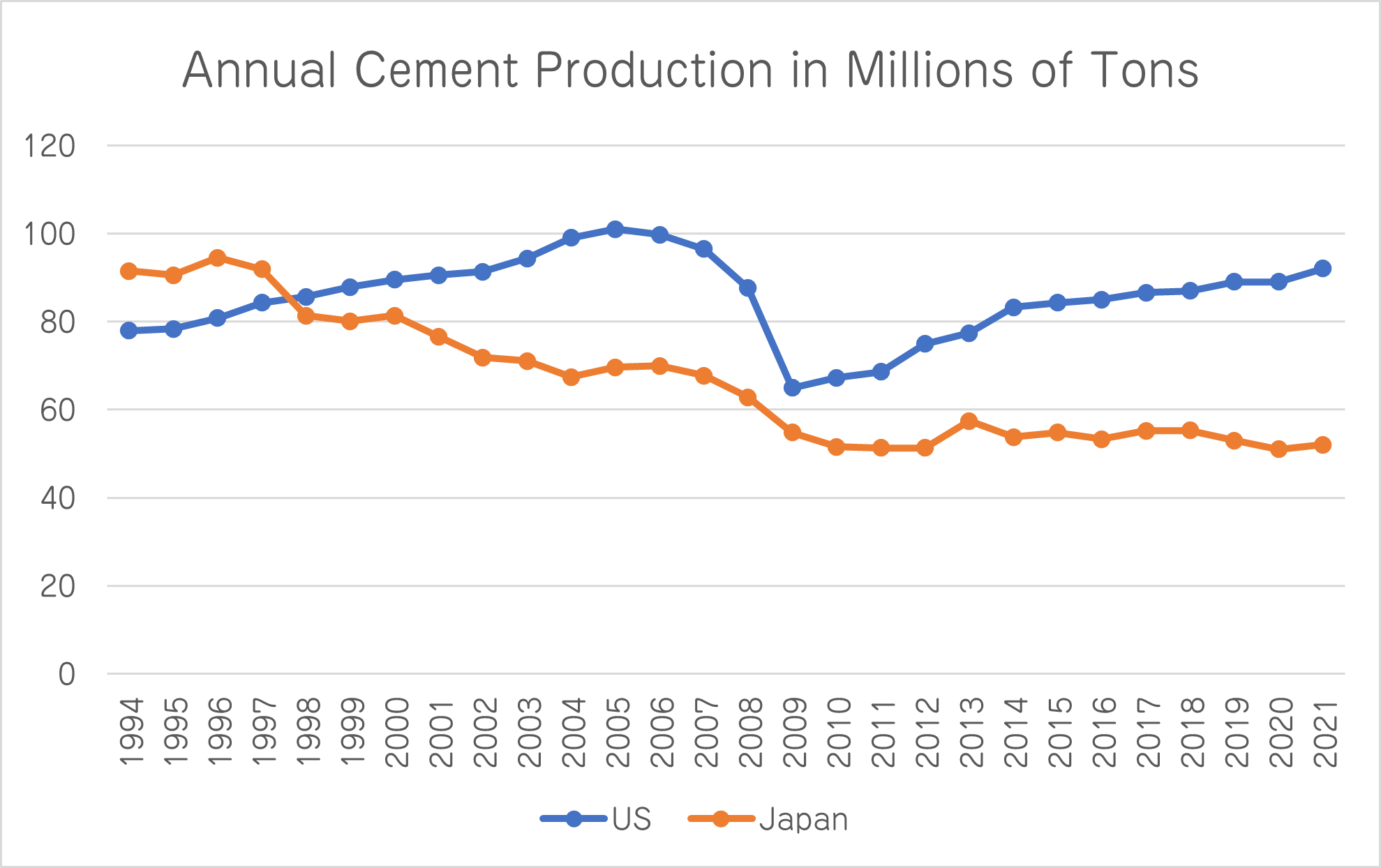

nobody keeps track of exactly how many hillsides have been covered by concrete in japan (probably because it would be such an overwhelming task), but you can look at the total cement production and compare with other countries to get a general idea. total cement production also has the benefit of covering other popular uses of cement in japan, like dams, riverbeds, and of course the ubiquitous coastal tetrapod. so, according to kerr, in 1994 japan produced 91.6 million tons of concrete while the US only produced 77.9 million tons. yes, japan is about the size of california and yet they produced almost 20% more concrete than the entire US. kerr writes: "this means that japan lays about thirty times as much per square foot as the united states". this is even more insane when you consider that in 1994, japan was already well on its way into a deep recession, so much so that the nineties were deemed "the lost decade".

how have things progressed since 1994, though? the USGS publishes annual statistics on world cement production, which i used to make the chart above. japanese cement production has steadily fallen since peaking at 94.5 million tons in 1996, but seems to have stablized for the past decade around 50-55 million tons. maybe the economy started finally catching up or they ran out of stuff to cover, and now they are at "maintenance" level. meanwhile US production made modest annual gains until a precipitous drop starting in 2007, attributed in the reports to the recession. it feels almost too obvious and logical compared to to what happened to the japanese cement industry in response to the recession in the nineties. in any case, things are certainly a bit better as japanese cement production has dropped by half from its peak, but on a tons-per-square-mile basis, this is still fifteen times more cement than the US is currently producing (incidentally, in absolute terms still slightly less than japan's peak, too).

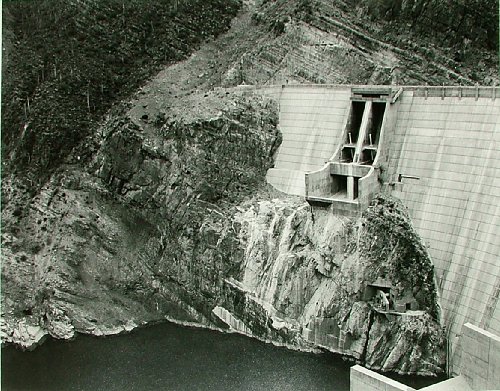

certainly not all of that concrete is going to the hillsides, though. as we saw earlier, another major usage is water control structures: dams, weirs, channels, artificial riverbeds, diversion canals, and levees. kerr reports that all but three of japan's 113 major rivers have been dammed or diverted by 1997. this comes out to around 2,800 major dams, and kerr claims that the japanese government was eager to add another 500 to that number in an era when other countries were starting to take down dams after becoming aware of the environmental costs. as far as i can tell, though, the ambitious dam building plans never ended up coming to fruition and there are still approximately 2,800 major dams in japan.

certainly not all of that concrete is going to the hillsides, though. as we saw earlier, another major usage is water control structures: dams, weirs, channels, artificial riverbeds, diversion canals, and levees. kerr reports that all but three of japan's 113 major rivers have been dammed or diverted by 1997. this comes out to around 2,800 major dams, and kerr claims that the japanese government was eager to add another 500 to that number in an era when other countries were starting to take down dams after becoming aware of the environmental costs. as far as i can tell, though, the ambitious dam building plans never ended up coming to fruition and there are still approximately 2,800 major dams in japan.

but while dams are easily the largest structures built on waterways, they are far from being the only ones. if you also count structures like weirs that are below the "official" dam height, the estimates balloon to well over 100,000. conducting a basic survey using google maps (a favorite pasttime of mine), you can see all sorts of strange structures on even modest rivers. at random i first chose to inspect the humble shomyo river in toyama prefecture, which could arguably be called just a large creek. below the scenic 350-ft waterfall, the river runs for roughly five miles before flowing into and joining the jouganji river. just going down that five-mile stretch, i counted SEVENTY weirs that were clearly visible in the satellite imagery. on top of that, in some sections they were also accompanied by concrete walls. as far as i could tell absolutely nobody lived in this area, it was just a random relatively-remote river valley.

but while dams are easily the largest structures built on waterways, they are far from being the only ones. if you also count structures like weirs that are below the "official" dam height, the estimates balloon to well over 100,000. conducting a basic survey using google maps (a favorite pasttime of mine), you can see all sorts of strange structures on even modest rivers. at random i first chose to inspect the humble shomyo river in toyama prefecture, which could arguably be called just a large creek. below the scenic 350-ft waterfall, the river runs for roughly five miles before flowing into and joining the jouganji river. just going down that five-mile stretch, i counted SEVENTY weirs that were clearly visible in the satellite imagery. on top of that, in some sections they were also accompanied by concrete walls. as far as i could tell absolutely nobody lived in this area, it was just a random relatively-remote river valley.

then, there are the tetrapods. the stalwart, omnipresent concrete guardians of japan's coasts. it might feel like they're everywhere if you've been to japan, but how bad is it really? well, kerr writes that taking into account every type of coastal barrier including tetrapods, by the year 2000 over SIXTY percent of the shoreline has been covered in concrete. in a somewhat more recent online article covering tetrapods specificallycheck out the article if you want to learn more about tetrapods, stephen hesse uses official government numbers to put the percentage of the coastline that has been altered at nearly fifty percent.

then, there are the tetrapods. the stalwart, omnipresent concrete guardians of japan's coasts. it might feel like they're everywhere if you've been to japan, but how bad is it really? well, kerr writes that taking into account every type of coastal barrier including tetrapods, by the year 2000 over SIXTY percent of the shoreline has been covered in concrete. in a somewhat more recent online article covering tetrapods specificallycheck out the article if you want to learn more about tetrapods, stephen hesse uses official government numbers to put the percentage of the coastline that has been altered at nearly fifty percent.

so now that the extent of japan's concrete craze has been firmly established, we come to the Big Question: why? is all of it really neccessary for "safety" and "development"? there are many reasons to be suspicious. in the case of the coastal concrete casing, kerr asserts "nobody in their right mind can honestly believe that japan's seacoasts began eroding so fast and so suddenly that the government needed to cement over 60 percent of them." in fact, according to kerr, there is growing evidence that the wave action on tetrapods may actually be accelerating erosionhesse also brings up the point that coastal erosion may also be increasing due to lack of sediment replenishment because, guess what, rivers and creeks upstream have had their banks hardened with concrete and thus aren't washing sediment down to the coast. as a result, starting with maine in the 80's, multiple states including oregon, both carolinas, rhode island, and texas have banned or imposed significant restrictions on not only tetrapods, but all varieties of shoreline armoring. a usgs article on shoreline armoring gives the rationale: studies show shoreline armoring increases erosion of fronting AND adjacent beach in addition to impacting marine habitats and organisms. the benefit? property values are maintained for the waterfront property owners, although it appears to actually lower property values "a few rows in-land".

there are also the dams to consider. kerr writes that the dams are justified by the construction ministrysince publication, absorbed into the ministry of land, infrastructure, transport and tourism (MLIT) in order to address impending water shortages. however, the water usage projections were calculated in the 50s and never revised, so dams continued to be built well into 90s based on those figures despite the fact that they were overstating current national water demand by eighty percent, according to a 1995 newspaper investigation. this, as it turns out, was a common pattern. in 1997, the government began reclaiming isahaya bay near nagasaki, japan's last major tidal wetland, based on a plan from the 60s to provide new fields for farmers. by 1997, of course, these new fields weren't really needed because the number of farmers in the area had dwindled since the plans had been established, but they plowed along anyway. something almost identical occurred with shimane prefecture's plan from 1963 to fill in part of lake nakaumi, even as the few remaining farmers begged them to stop as it would harm the lake's water quality. in this case, there was a "happy" ending, as the reclamation stopped in 2000 at the 40% mark after a review of the most wasteful public-works projects.

a handful of isolated incidents could easily be attributed to mere incompetence, but such a bonanza of boondoggles points to a systemic cause. according to kerr, the construction industry in japan makes up a disproportionately large portion of the economy, to the point where japanese commentators refer to the country as a "construction state"土建国家. how did the construction industry become so bloated? kerr identifies the source as the enormous government construction spending and subsidies, with public works taking up 40% of the national budget, as opposed to 8-10% in the US.

of course, now the question is why does the japanese government spend so much on infrastructure and public works, even when most of it is clearly not needed? as with all boondoggles, there's a simple answer: Money. specifically, public money finding its way into the pockets of politicians and bureaucrats. kerr describes the process like so:

Construction Ministry bureaucrats share in the takings at various levels: in office, they skim profits through agencies they own, and to which they award lucrative contracts with no bidding; after retirement, they take up sinecures in private firms whose pay packages to ex-bureaucrats can amount to millions of dollars. The system works like this: the River Bureau of the Construction Ministry builds a dam, then hands its operation over to an agency called the Water Resources Public Corporation (WRPC), many of whose directors are retired officials of the River Bureau. The WRPC, in turn, with no open bidding, subcontracts the work to a company called Friends of the Rivers, a very profitable arrangement for the WRPC's directors, since the own 90 percent of the company's stock. Hence the ever-growing appetite at the River Bureau for more dam contracts. When it comes to road building, the four public corporations concerned with highways annually award 80 percent of all contracts to a small group of companies managed by bureaucrats who once worked in these corporationsthe term for these bureaucrats is "amakudari" (天下り). Similar cozy arrangements exist in every other ministry.

kerr points to a number of reasons why japanese bureaucrats and politicians are able to get away with corruption on such a scale. a key part of it is that the government is remarkably unaccountable to the public. the bureaucratization is such that democracy in japan is mostly just a "ritualistic" veneer. it's not even particularly convincing, as the liberal democratic party has been in power in the government almost continuously since being established in 1955, only losing power briefly in 1993-1994 amid the unprecedented economic downturn following the collapse of the asset price bubble, and then again from 2009 to 2012the liberal democratic party is reliant on the rural agricultural vote to stay in power, which it keeps through a policy of special rural subsidies. most of those funds are earmarked for construction, which is why the "damage" tends to be worst in the countryside. many rural municipalities in fact beaome dependent on them for their budgets and to prop up stagnating local economies, and thus had to continuously build and spend all the money every year so their subsidies wouldn't be reduced. as such, elected officials largely uphold the status quo, and unelected bureaucrats are beholden only to the ministry of finance, which determines their annual budgets. as is quite common in bureaucracies, the japanese government bureaucracies became devoted only to perpetuating themselves by preserving their own budgets, by spending their entire budget each year so that it never gets cut. all that money has to go somewhere, and thus it ends up financing various unneccesary boondoggles and consequently lining the pockets of whole networks of officials. kerr reports that despite massive changes to the country over the course of three decades, the proportional allotment of construction funds going to each ministry is almost exactly the same in 1999 as it was in 1965.

while the government may be unaccountable by design, the whole system only works so well because the japanese public for the most part doesn't speak out. kerr lays the blame for this primarily on the educational system, devoting an entire chapter to it alone.

but there is also the fact that to some extent, the excesses of the construction state are what the japanese public wants. most obviously, the bloated construction industry has become a massive part of the economy, and in the late nineties, experts estimated that one in five jobs in japan depends on construction, directly or indirectly. this is especially true in rural areas, kerr relates how nearly everyone in the remote iya valley where he lived had become construction workers by 1997, relying on the steady flow of construction subsidies.

then, there's the psychological angle. while having by all accounts clearly established itself as a highly developed country and global economic power by the late eighties, the japanese national psyche was still saddled with an inferiority complex. it's somewhat understandable, considering that at that point the country had been in post-war shambles within living memory, only several decades before. so, just like the nouveau riche do when they go off buying expensive flashy cars and clothes, for the nouveau riche country this means spending money on fancy infrastructure projects and monuments to "look" and "feel" rich. meanwhile in secure, old money america, reagan was eagerly cutting government spending and taxes, letting infrastructure fall apart while people bought bigger houses and cars, confident in their wealth.

finally, there are the deeper cultural attitudes. while earlier i established the "reverence for nature" in traditional japanese culture, that is only part of the story. sure, japanese gardens are focused around bringing out the beauty of their natural elements, but this is accomplished only through rigid control of nature. the aesthetic order and "cleanliness" that give the traditional japanese garden its charm are wholly artificial. what happens when modern technology enables this methodology to be extended beyond merely creating aesthetic gardens? kerr quotes senior japanologist donald richie: "what's the difference between torturing a bonsai and torturing the landscape?"

the result is that when faced with important new considerations like "safety" and "development", there are few qualms with taking extreme measures against nature to address them. modern technology has equipped the japanese with devastating new weapons that they can use to finally turn the tides in the war with nature. wait, what? yes, below all the typical feel-good "living in harmony with nature" stuff, there's a recently-ascendent national myth of japanese history being that of a constant struggle against nature in the form of natural disasters and such, characterizing japan as particularly harsh place to live (another example of japanese exceptionalism?). kerr summarizes these attitudes in a quote from a publication by the construction ministry's river bureau:

Earthquakes, volcanoes, floods, and droughts have periodically wrecked havoc on Japan. For as long as Japanese history has been recorded, it has been a history of the fight against natural factors... Although Japan is famous for its earthquakes, it is perhaps water-related problems which have been the true bane of Japanese life. In the Japanese islands, where the seasons are punctuated by extremes, extremes which have have required people to take vigilant precautions in order to assure survival, water is a constant issue.

the government's job, then, is to take on the role of the gardener and try to reign in nature across the whole country. perhaps you're familiar with the common japanese word "kirei", which means both "lovely" and "neat and tidy". it's a word that easily comes to mind when praising a japanese garden, but it's also one that kerr observes japanese people using to describe a freshly concreted hillside or riverbanki propose that when used to describe concrete structures, we write キレイ instead of 綺麗. the tetrapods are not without their fans either. that hesse article from earlier includes an interview with a young art student who i guess you could call a "tetrapod otaku" that makes mini-tetrapods and professes his love for tetrapods is because they are artificial and do not fit in with nature. a different tetrapod article i read talks about a salaryman (who prefered to remain anonymous) with a side hustle of selling plush tetrapods. even foreigners are taken in by the concrete illusion of modernism in japan says kerr, "... they can have no idea of the mysterious beauty of the old jungle, rice paddies, wood, and stone that was paved over". god only knows the amount of japanese countryside photos (edited so bright that they looked washed out) with plenty of conspicuous concrete that i've stumbled across and briefly thought "AH, glorious nippon, so advanced and so aesthetic!"i won't deny that there's a certain je ne sais quoi that aged, unmaintained concrete gains once it's acquired a fine patina of weathering. is this some twisted form of wabi-sabi?

kerr concludes dogs and demons on a pessimistic note. although my focus here was mainly on construction, the book also contains many chapters detailing malaise in many aspects of japan, such as in the economy, information, urban planning, tourism, education, culture, and internationalizationthe section on information is particularly juicy and overlaps with a lot of themes in my thinking w/r/t "the map not being the territory". fixing a collapsing economy is quite difficult on its own, but it becomes a completely different beast when all your numbers are off thanks to widespread "cosmetic accounting", conducted in order to save face. in some cases the government itself was even complicit, and it was many years before the true extent of the financial crisis was known. one of the most prescient parts, though, was about the dismal state of safety in the nuclear industry, a warning which was not heeded and thus resulted in tragic consequences ten years later in the fukushima nuclear disasterit's a bit ironic how the japanese spent decades cementing over miles of coasts and yet somehow failed to put enough in maybe the only place where it would end up mattering, right in front of a nuclear power plant. at the very least they made up for it afterward by cementing the seabed all around to prevent the escape of radioactive materials... kerr believes that the root cause underlying the issues in all of those areas is a fundamental disconnection from reality. rivers were dammed to provide water that wasn't needed, hillsides were concreted to prevent landslides that never came in places on roads people never take, farmland was reclaimed that farmers didn't need, coastlines were covered in ineffective tetrapods to defend against extreme erosion that wasn't happening. other examples from the book that we haven't seen here yet are the roads that go nowhere, the lavish hotels and monuments built for tourists that would never come, businesses and even the government cooking books to hide the true extent of debt, and so on. kerr says he dreams of change in his heart, but ultimately remains skeptical as the issues are both long-term and chronic.

dogs and demons was published a little over 20 years ago as i write this, so we can check in and see how things have progressed since then. i know right off the bat that the chapter on the stagnant tourism industry is outdated by now. before getting clobbered the past couple of years by covid, the number of international tourists to japan was rising rapidly each year. it's kind of hard to believe now, but for decades japan was one of the least visited countries for its size and population, a trend that only reversed around ten years ago. according to annual visitor data published by the JNTO, there were 5.2 million international tourists in 2003, 8.6 million in 2010, and then 31.8 million in 2019. i recall reading some blog posts from 2010 by an expat in japan decrying the sorry state of international tourism, and visiting some dubious tourist attractions across the country, he observed that they all seemed to be trying to play the "china card", capturing tourists from the nearby and rapidly-expanding chinese middle class. this seems to have actually played out well, because a good portion of the increase in tourism to japan has been thanks to chinese tourists, who make up a third of the total tourists visiting japan. i don't know to what extent you can attribute this to anything other than dumb luck of being near china while it gets wealthier. the other major factor driving tourism growth, the huge popularity of japanese media overseas (you know what i mean), seems to have been a complete accident as well. the japanese were phenomenally reluctant to export most anime, leaving the job to janky cash-strapped foreign licensors or devoted fans subbing and distributing via piracydid you know crunchyroll started off as a piracy site?. thanks to them, it's now bigger than ever, and the japanese are getting a windfall not only in terms of moving merchandise, but tourism as well.

i could spend a lot of time doing my own research on how things have been coming along since dogs and demons was published... or i could try to get an update from the horse's mouth, as it were. maybe one of these days i'll have the guts to send an email or something, but for now i was able to find an interview on youtube with alex kerr from earlier this year where the interviewer asked alex about his opinions on how dogs and demons holds up today. he immediately identified the section on tourism as being largely outdated now, and talked so much about the current tourism situation that he never got to re-evaluating any other parts. he sees the increase in tourism as largely a good thing, probably the only thing that can revive the economy in rural areas, the same ones that were turning to government construction money for survival after the collapse of forestry or other related industries. however, he also said that japan is starting to have an issue with OVERtourism in popular destinations like kyoto. always another demon...

[expand here?]

what does the future look like for japan, if the concrete craze continues? to close off a chapter, kerr relates some of the grandiose proposals construction companies put forth right as concrete production was peaking and the future seemed rosey (concretey?). a particularly far out one involved a concrete conquest of the final frontier, the moon. more down to earth, kajima corporation proposed a "stacked structure, a so-called Dynamic Intelligent Building, which consists of several fifty-story structures piled on top of one another". meanwhile, an 800-meter skyscraper on pillars above a city was proposed by shimizu corporation. seems great, but currently japan is heading into the mother of all demographic crises. conceivably, there may not even be anyone left to enjoy all that concrete. this is why i believe another -mizu offers the most compelling vision of future japan: