well, time to throw my hat into the ring. i debated doing this for a long time – there are more than enough “japanese learning guides” out on the internet already and i'm not sure that's a good thing. in fact, if you have read more than a couple of them, cease reading this AT ONCE and go read something in japanese instead. maybe i should have written this IN japanese.

regardless, i sincerely believe that i have some novel insights (hot takes) to bring to the table, stuff i've never seen discussed anywhere. this is also not really a guide, it's more of a series of loosely-connected rants and observations, some of which people who have to put up with me in person have already heard. most are focused around the "softer" parts of the learning process, the underlying mindset and mental models. some are motivational and some are demotivational, and honestly i don't know if half of this stuff is even useful for learning, i just wanted to write it down somewhere.

what are my qualifications? according to my anki statistics i have been at it for 77 months. based on a completely unscientific analysis of online vibes, i believe that i have made it further than at least 95% of people who have tried to learn japanese. i still have a long way to go, though i’ve reached a very good position past the initial steep learning curve where i can comfortably read pretty much every manga i’m interested in. technically i also minored in japanese, but that means very little. more on that later.

contents

- THE ROAD AHEAD IS LITTERED WITH BODIES

- GIVE UP NOW

- YOU GOTTA WANT IT

- THE SKILL TREE

- THE RESOURCE CURSE

- APPLIED SUBOPTIMALISM

- SUBOPTIMALISM IN PRACTICE

- THERE ARE NO SHORTCUTS

- WHY "I'VE BEEN STUDYING JAPANESE FOR X YEARS" IS MEANINGLESS

- JAPANESE CLASSES: AN HONEST REVIEW

- MISER MOTIVATION

- “I AM GOING TO JAPAN SOON AND NEED TO LEARN SOME JAPANESE FAST!”

- A WARNING CONCERNING "COMMUNITIES"

- ONE NEAT TRICK

- JESUIT JAPANESE

- THE SECRET FORBIDDEN TECHNIQUE

THE ROAD AHEAD IS LITTERED WITH BODIES

Upon arriving in Japan in 1549 to convert the natives to Christianity, it is not surprising that St. Francis Xavier ran into communication difficulties. While he was positive overall about the Japanese people, he came up with a remarkable theory about their language. He found communication so challenging that he wrote of his belief that the Japanese language had been planted by the Devil in order to stymie Christian missionary work.

— the unpaywalled portion of a japan times article i found while researching jesuits in japan

the biggest difficulty most people have with learning japanese is that it's really hard (tautology for emphasis). according to some sources, it may be the single hardest language to learn as a native english speaker. there's many ways to compare language learning difficulty, but here's one observation i keep coming back to from my time in college language classes: friends in fourth-year french were reading proust in the original, meanwhile in fourth-year japanese you’d be hard-pressed to find anybody who could comfortably make it through dazai’s short story run, melos!, commonly assigned to japanese middle schoolers.

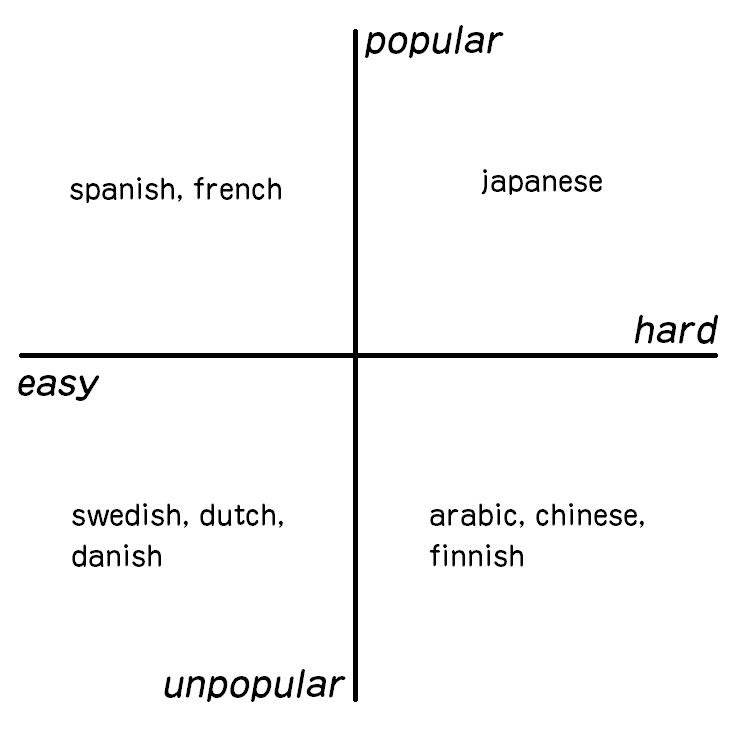

yet, unlike other super-difficult languages like arabic or chinese, the difference with japanese is that there are tons of people who want to learn it (the reason for this is left as an exercise for the reader). from the perspective of a native english speaker, if you sorted languages into quadrants by learning difficulty and learning popularity, the result would come out something like the graphic at right. the examples listed in each quadrant aren't exhaustive, except for in the top right: i cannot think of a single other language besides japanese that is both popular and difficult, except possibly korean (a relatively recent development). even then, if the axes were scaled, japanese would be in the top right corner whereas korean would be somewhere closer to the middle.

yet, unlike other super-difficult languages like arabic or chinese, the difference with japanese is that there are tons of people who want to learn it (the reason for this is left as an exercise for the reader). from the perspective of a native english speaker, if you sorted languages into quadrants by learning difficulty and learning popularity, the result would come out something like the graphic at right. the examples listed in each quadrant aren't exhaustive, except for in the top right: i cannot think of a single other language besides japanese that is both popular and difficult, except possibly korean (a relatively recent development). even then, if the axes were scaled, japanese would be in the top right corner whereas korean would be somewhere closer to the middle.

the fact is, japanese is in a unique position as both one of the hardest languages to learn and one of the most popular to try and learn. the consequence is that when studying japanese nowadays, the road ahead is littered with the bodies of those who couldn’t make it, especially near the start. this is in contrast to "uncool" difficult languages like arabic or chinese, where the uncoolness serves as an initial filter for casuals, which means people who set out to study those languages are more likely to have sufficient motivation or dedication to "make it".

GIVE UP NOW

what's even the point of learning japanese? everything worthwhile is already being translated into english almost right away. the rest can be handled by ai translation tools, which are getting better every day, dramatically so in the past year. there are already demos of software that can flawlessly translate videos of people speaking from one language to another, perfectly matching the original voice and lip flaps. in the next few years you might be able to go to japan wearing an earpiece that translates everything you hear, wearing a vision pro headset that instantly translates any text you see. the only downside will be that you look like a dork. the translation tools are getting so good recently that i honestly don’t know if i would still study japanese if i started today.

if that blackpill doesn't filter you, then welcome aboard. you might just have what it takes.

YOU GOTTA WANT IT

there’s a reason every high school kid in america manages to sit through years of spanish classes without learning any of it: they simply do not care. even though they go through the motions, doing all the assignments meant to teach the language and passing all of the tests meant to show that they’ve learned the language, they manage to avoid doing so. never doubt the human mind’s astonishing capacity for willful ignorance. the takeaway is that nobody can truly learn anything unless they want to, an impenetrable barrier schools have been hopelessly flailing against for centuries (but enough about my pet topics).

so, to learn japanese, you either gotta want it or you gotta need it. how much do you have to want it? the trouble is that japanese is so difficult that you've got to REALLY want it. there are a lot of things you can casually pick up with just 10 minutes of light practice a day, or an hour here or there. if you try to learn japanese with only that level of dedication, you might be good enough in the midst of demented confusion to thank the nurse in japanese at the retirement home for unplugging life support and ending your misery, to which she replies "oh, is that japanese? don't hear that much anymore... shame what happened to them..." finally reach intermediate level on your deathbed. it's not a race but still, it's not like you have infinite time.

learning japanese is the kind of thing that requires deep passion, obsession, mania. in a word: insanity. you must be able to channel deep autistic energies on the level of hobbly tunnellers, prolific wikipedia editors, people who build computers in minecraft, the cardboard cutout guy, programmers who code in assembly for fun. there has got to be something, ideally a couple of somethings, in japanese culture that would motivate you to push through hundreds of hours of unforgiving grind to learn the language.

there are plenty of options because japan is both insular and a cultural powerhouse, animanga being an obvious one. i’ve also come across people learning japanese because they’re really into video games or japanese cars or sumo or fashion or even the pro wrestling scene (based?). a limited interest can only take you so far: a friend of mine was basically only interested in japanese because of pokemon and fire emblem. his dedication to those two things was nothing to scoff at, the exact kind of energy you need to learn japanese. the issue was, they didn’t go deep enough into japanese to carry him far into learning it. pokemon games for kids so they’re easy to understand, and fire emblem isn’t too bad either once you’ve learned to decipher the pixelated kanji for every type of medieval weapon. so, my friend got up to a point where he was comfortable playing both games in japanese, and then stagnated. he wasn’t interested enough in any other part of japanese culture that could carry him further, that had more difficult material. diagnosis: not wanting it hard enough; prognosis: never gonna make it.

THE SKILL TREE

japanese can be divided into five distinct skills, which fall into two categories. there are the consumption skills, reading and listening; and the production skills, speaking, writing, and handwriting/calligraphy. there is some general overlap between the skills, e.g. learning vocabulary will help you across all of them, but for the most part i view each skill like a seperate branch of a skill tree, where each one has to be levelled up separately by doing the appropriate trainingmost of the time the "appropriate training" is fairly obvious, however there are a few deceptive situations where you think you're practicing one skill but in reality you're relying on a different one. for example, i've found that watching anime with japanese subtitles becomes primarily reading practice. to get real listening practice, you have to take off the training wheels and go in raw.. i think this kind of skill divide exists within many languages, although it is particularly acute in japanese due to the enormous gap between the spoken and written language, which can almost entirely be attributed to the existence of kanji. there is a huge difference between having to learn 26 alphabet characters vs. 46 hiragana, 46 katakana, and then on top of that 2,000 distinct kanji characters.

what the existence of the skill tree implies is that it's possible to create different japanese language ability "builds", based off of how you allocate your study or practice time. most classes and courses try for a balanced approach, evenly dividing study time into each of the five branches, what you might call a "generalist" or "well-rounded" build. you encounter a little more diversity when it comes to people who study independently, some of whom inadvertently end up with a very lopsided skillset due to, say, focusing exclusively on consumption rather than production.

what i realized quite early on is that there is absolutely nothing stopping you from doing something like that on purpose, creating a specialized build based off of your own personal goals. there's no reason you can't ignore all the other skills and advance super quickly in one specific one by putting all of your skill points into it. everyone has different priorities and if you can boost your ability to do what you care about at the expense of neglecting something that you don't care about or that's useless to you, then why not? for example, i love reading and have an irrational fear of speaking to foreigners in their native language, so i simply ignored speaking completely and focused everything on reading practice. i can't really hold a conversation in japanese (except for a handful of times when i was extremely drunk), but i can damn well read.

out of all the skills, i would say handwriting/calligraphy is the least useful and probably the easiest/best to completely ignore. everybody just uses IMEs on phones and computers now to write japanese, and even many japanese people are starting to have difficulty writing out most kanji by hand. most learning courses that include handwriting kanji usually only do so because it is believed that it makes learning them easier, however that doesn't mean it's a requirement for remembering them. while isolated kanji study like i've done will leave you in an odd situation where you can't write or even picture in your head 99% percent of the kanji you can recognize and read, at no point has it ever become a disadvantage. handwriting-defenders sometimes concoct contrived situations in which it is useful to have that ability, though nearly all of them are easily neutralized by the fact that everyone nowadays carries around a smartphone.

this also feels like the most appropriate section in which to mention that there's a further skill/domain separations with regards to vocabulary and style in different types of media and genres. it's not as pronounced as the divide between the five main skills, but it's noticeable. the vocabulary, grammar, and register used in a slice-of-life manga will differ from that of a newspaper or even from a manga in a different genre, so if you get really good at reading from going through tons of slice-of-life manga, you will likely encounter difficulty trying to read the average newspaper. there is also a difference between the vocabulary and grammar used for dialogue vs. descriptive language, which means that focusing only on media that is primarily dialogue like manga and anime can result in deficits when swapping over to light novels, which rely on descriptive language in the place of images. visual novels land somewhere in between, they tend to be heavy on dialogue but quite a bit of descriptive language gets in as well.

THE RESOURCE CURSE

the popularity of japanese, especially among computer nerds and other overly-online people (again, exercise left for the reader), means there’s an abundance of learning resources out there on the internet. i would not be surprised to find out that it has the most online learning resources of any language. there’s approximately ten thousand different guides, websites, apps, videos, podcasts, etc. for learning japanese. half of the personal blogs on the internet have a post about “my japanese learning journey” and the other half are still in the process of writing it, whether they know it or not (this site has finally transitioned from the latter category to the former).

sometimes i go over to the “r/japaneselearning” subreddit for some comic relief and i see a shocking amount of submissions saying “i was unsatisfied with all the learning tools out there so i built my own webapp to do xyz, try it out here”. some of those sites are complex or interesting enough from a technical standpoint to make it to the front of orange reddit. i don’t think there’s any other language learning “community” in which this sort of thing happens on a routine basis. meanwhile, for some languages you are lucky to find two poorly-scanned textbook pdfs and one crappy flashcard deck online.

to the naïve observer, the preponderance of resources might seem like a good thing. with so many options, so many tools, it should be easier to learn than ever, what could possibly go wrong? the thing is, i think there’s so much that it's actually overwhelming and ultimately a hindrance. deciding which resources to use becomes such a gargantuan task that you give up even before you start, a classic case of analysis paralysis. choosing is difficult because naturally everyone has a sales pitch claiming their course or resource is “the best”, the most efficient, using the latest technology, supported by research and sciencesometimes you look into it and the "science" is just an unproven theory a guy made up in the eighties. something called the "input hypothesis" seems to do a lot of heavy lifting as the "scientific" basis for a lot of courses. remember, the words "theory" or "hypothesis" = a guy just made it up. language learning research is plagued by many of the same issues that affects research in other "soft" sciences like psychology, such as questionable operationalization, dubious experimental conditions, poor statistical analysis, and small effect sizes. thus, most of it can safely be disregarded. pretty much the only important result that's stood up to scrutiny is "spaced repetition is good for long-term rote memorization". translation: "anki = good for learning kanji". and hundreds of satisfied customers, approved by the emperor himself. some grifters and bad actors go even further and engage in slander and fearmongering, instilling irrational fears that choosing the wrong course may not just slow your learning but actually harm it. their course is the only true path for learning correct japanese, those other courses will set you back or even permanently ruin your japanese.

even if you manage to finally choose a path, the danger is still out there. it's possible to fall into what i call the “eternal beginner” trap, a cycle of starting one course or guide or new anki deck and giving up partway through, coming back after a few months and deciding to start over again using a different approach, giving up again, and so on until you've gone through a dozen different courses, reviewing the same basic material over and over again, never making it to intermediate level, believing it’s simply because you haven’t found the right course or tools yet. many such cases...

the abundance of resources can also serve as a great excuse for procrastination. you can spend an entire lifetime trying out different tools, reading all the japanese learning guides that have been published on the internet, or videos on the finer points of grammar. it takes less effort than trying to engage with something in japanese, and all the while you can convince yourself that you’re “studying”. it’s akin to the people who become obsessed with researching and buying the best gear for a hobby, which then sits in the garage in pristine condition because then they never actually go out and use it for said hobby. maybe they spend hours reading up theory, but then they go out into the real world they flounder. what’s the point? you need real-world experience

APPLIED SUBOPTIMALISM

as applied to learning japanese, the key insight of suboptimalism is that there is absolutely no need to stress about selecting the most efficient course or the most effective tools. there are as many ways to learn japanese as there are people who have learned japanese, nearly every path can get you there eventually. with sufficient dedication, you can pave over the inefficiencies in any course of study with brute force, putting in more raw hourage of study and practice. there is no use in wasting too much time searching for the perfect course because like in many fields, there are no magic bullets in language learning. consider: if there really was a course dramatically better than all the others, it would easily stand out from the crowd. this is not the case, therefore the differences in efficacy between most courses must be minor enough so as to be indistinguishable in practice. theoretically an "optimal" course may still exist, but selecting it over the others would only result in a modest efficiency gain. the gains might be so minor as to cancel themselves out due to the amount of initial research you'd have to undertake to even find it in the first place, and someone who just spent those extra hours practicing would end up at an identical level.

with the suboptimalist approach, since you're playing the long game, the most important aspect of method selection is choosing one that you think you can stick with. this will vary from person to person, some people require rigorous structure and a set schedule, others are fine with a more freeform approach. overall, though, i think it's best to keep it simple - the less friction studying involves, the better. for example, i resisted installing the anki flashcard app on my phone for reasons that are now obscure to me (i was doing some kind of linux thing back then). then i finally relented, and suddenly my anki usage got a lot more consistent because i could pull out my phone and do a few reps whenever i had some free time (i also stopped staying up until 2 am at night crunching out anki reps on my laptop at the last minute). it wasn't long before i stopped using anki on the computer entirely. the same ease of access that makes phones so dangerous for doomscrolling can also turn them into powerful tools.

SUBOPTIMALISM IN PRACTICE

in order to demonstrate that you can get somewhere eventually sticking to any dumb inefficient method long enough, i'll speak a little bit ahere about my own technique, which developed out of my own nearly-pathologic inability to install plugins, scripts, apps, and add-ons. when people would casually discuss modding games like skyrim with me as if it's a relatable thing everyone does, i would smile and nod along while on the inside not following along at all because i have never installed a single mod for most of those games, and if i have it's maybe one or two minor ones.

i swear this is entirely true, literally 95% of my japanese learning is based on jisho.org. it's not perfect but it has a lot going for it: no ads, clean interface that never changes, doesn't try to be too many things at once, can access it from anywhere with internet. it's primarily a dictionary but you can even use it for grammar if you're brave enough, search any unfamiliar particles and it will give a brief usage overview. the biggest downside is that the handwriting search function is completely unusable, it's almost offensively bad and they ought to remove it rather than keeping it in its current state, so i exclusively use the radical search for any unfamiliar kanji, individually picking out the radicals i see in it until i find the kanji i'm looking for. the process is phenomenally slow. a good portion of the other 5% consisted of anki, where i made all of my cards by hand, copy and pasting from jisho into a custom card format with only 4 fields to make things faster. if i were to do it over again, i'd remove one of the fields (part of speech) because i never paid attention to it anyway.

all that plus hundreds of hours of reading is more or less my entire japanese learning method. goes to show you can get somewhere doing much anything through pure pigheaded persistance.

THERE ARE NO SHORTCUTS

i think one reason some people get so caught up in shopping around for courses or learning methods is because they’re searching for shortcuts, that “one neat trick” that will let them avoid putting in any actual thought or work. perhaps in public they wring their hands about how “dystopian” elon musk’s neuralink implant thing is, but out of the corner of their eye they’re secretly tracking its progress and would be the first in line to get it put in if it can make you instantly understand japanese. they want to believe in fantasies like duolingo’s “you can become fluent in just 10 minutes a day” and “it works because we’ll keep you hooked using gamification and a cartoon owl that bullies you” (a little sad that 10 minutes a day is the best they can manage after years of developing these sophisticated techniques). most respectable courses are generally upfront about the amount of effort that will be required, however more than enough grifters have noticed the unmet demand for shortcuts and so they’ve muddied the waters with all sorts of quackery like sleep learning (huxley got a lot of things right but this wasn't one of them) and passive learning (“whitenoising”).

the solution is to accept from the outset that there are no shortcuts - if you want to learn japanese, you WILL have to put in the time and do the work. if you're unwilling to do so, then don't waste your time and don't even start. probably 95% of the variance in japanese ability i've observed can be solely attributed to amount of hours spent studying or practicing, with people who have done more almost always outperforming those who have done less. in japanese class it was always easy to tell which students did a lot of studying on the side, and which ones were phoning it in, only showing up to class and doing the homework.

WHY "I'VE BEEN STUDYING JAPANESE FOR X YEARS" IS MEANINGLESS

one thing you encounter often that appears to disprove the "time spent studying/practicing = skill level" theory is people who have been “learning japanese for 1 year” with wildly disparate skill levels. some can barely read hiragana and others are already working on their modernist novel in japanese. almost always, it turns out that this is because people can mean radically different things by “learning japanese for 1 year”, to the point where it’s almost useless as a comparison. on one end, you’ve got grindset guys studying 8 hours a day like it’s their full-time job, learning a hundred new words per day in anki, wolfing down a whole light novel before breakfast. on the other end, there’s people going almost comically slow, doing stuff like learning one new kana a week, or our old friends the “10 minutes of duolingo a day” guys. sometimes the people in each category aren’t who you’d expect; the NEET who could potentially spend all day studying is the one who can barely stomach a handful of anki cards a day, meanwhile the medical student with a part-time job is the one putting in 6 hours a day.

so, don’t feel disheartened when you come across someone who is way better than you but hasn’t been studying nearly as long. the majority of the time it’s because they’ve simply put in more hours of practice during that timeframe. if you had as many hours of practice as them, you would probably be at a similar level too. if you ever lose heart, it’s always easy to find people on the internet in the opposite situation, way worse than you even though they've purportedly been studying for longer. i’ve seen many people barely past beginner level say they’ve been studying japanese for “10 years” (usually you find out they’ve taken like an 8 year break in the middle of that span). sometimes they even LIVE in japan...

JAPANESE CLASSES: AN HONEST REVIEW

several months after i started learning japanese on my own, i finally decided to join a few of my friends and sign up for college japanese classes. they had been taking japanese since high school, but back in those days i had been too ashamed to sign up. ultimately i don’t think i missed out on much, though, because it seems that high school japanese proceeded at such a sluggish pace that its entire multi-year sequence was barely equivalent to one semester of japanese 101 in college. within a couple months i was already caught up academically to my friends who had been “studying” japanese for several years. i asked them what they had even been doing for so long in high school japanese, and from what they were able to recall my impression is that they just hung out and watched totoro (with english subs) every so often. it was more of a japan-themed club during school hours than a class for learning the language. final verdict on high school japanese (despite never taking it): good for socializing with other misfits interested in japan, bad for learning japanese.

irrelevant observation that i will never find another place to shoehorn in: the department instructors were all japanese and it was interesting to see all the japanese quirks they introduced to the program, like how seriously they took cheating on exams. they always made sure to reserve a lecture hall large enough for at least one empty seat between each student, randomly assigned seats, handed out two alternating versions of the test, and then patrolled the room like circling hawks. no other department took tests quite that seriously, at best they’d do only one of the above. the most distinctive part of it all was that before each exam you were required to copy out a statement at the top that said “I swear on my honor I am not receiving any outside assistance” and then sign it. i suppose they don’t know those kinds of stunts don’t work on today’s cynical american students, who just laugh it off before deploying their carefully-honed cheating techniques as usual.to be honest, although college japanese is certainly a significant upgrade over high school japanese, it’s not that much better in comparison to learning on your own. all the japanese i did outside of class made classes extremely easy, which at the very least padded my GPA with a load of A+’s (this is why i always report my cumulative gpa instead of gpa in major like some people do). i suppose one benefit of japanese classes over independent study is speaking and writing practice, which is difficult to do productively on your own. there were a lot of vocal/conversation exercises, and every so often we’d have to turn in a piece of writing to be corrected and returned by the instructor (though not with enough frequency to have much of an effect). the thing is, i have my doubts about how effective those oral exercises are, considering that you do almost all of them with your fellow classmates who suck at japanese. it’s not even close to the experience of speaking with a native speaker, who can effortlessly correct even minor mistakes and also provide excellent listening practice for you. if you’re so inclined, you could probably do a lot better than classes using the internet to get connected with native japanese conversation partners or pen pals.

eventually, i started to get frustrated with japanese classes for taking up my time with homework that to me was basically nothing but useless busy work, when i could’ve been doing something more productive like reading manga in japanese instead. another thing that annoyed me was the focus on aspects of the language i didn’t really care about, branches of the skill tree i deliberately chose to ignore during my independent study. most frustrating was all the time devoted to learning how to write kanji, something which i was absolutely positive would never be useful to me outside of having to pass the weekly kanji quizzes in class. the reading portion of the quizzes was always easy of course, but in order to waste the least time and mental capacity on the writing, i developed a technique in which i’d cram by writing the kanji over and over again in the hour before the quizzes, regurgitate them, and then promptly forget them until the megacram session before exams. many pages of my old notebooks are stuffed with wonky kanji from those sessions. fortunately, the structure of the classes facilitated my efforts by never expecting you to be able to write kanji after they appeared on a quiz and then the following exam, so i was free to forget them with no penalty.

overall i would have to say that japanese classes were a waste of time for me, and i decided not to continue on to the fourth-year sequence after finishing the third-year. the amount i did do was still sufficient to net me a minor in japanese, though. at best i think it should be seen as a supplement of dubious efficacy to independent study, and you shouldn’t expect to get very far if it’s the only japanese studying or practice you do. while i accept that there may be some people who are better suited to learning methods with lots of hand-holding structure, i feel like anybody can learn japanese independently if they want it hard enough, and can’t help but feel that more often than not japanese classes are used as a crutch, yet another excuse for procrastination and avoiding putting in the work on your own. people convince themselves that they can only learn through classes and “just don’t have the time or the money for them right now” so learning japanese gets put on hold indefinitely, or maybe they start classes but think “well i’m already putting in enough effort by taking japanese classes so i don’t have to study more than that.”

MISER MOTIVATION

there are enough free resources online that it’s entirely possible to learn japanese without spending a dime, even if you completely avoid piracy. many such learners are oddly proud of their ultra-cheapskate status, and sometimes you get the feeling that there's some not-entirely-rational matter of honor or principle behind it because they will insist that you should do the same for whatever reason, even if you’re making the big bucks and can afford to pay for a fifteenth subscription service. although i'm in the "haven't spent a dime" crew (with the exception of college japanese classes), i don’t think there’s anything inherently bad about paying for a course like wanikani. in fact, i think there might actually be some benefit in doing so if you’ve got the right personality type. if you’re like me and always trying to get the maximum value out of your money on the rare occasions you spend it, paying for a course may help motivate you to study so that you get your money’s worth. you probably already know if that describes you or not – be careful if you think you might be of the opposite "aspirational" archetype, who have no problem paying for a monthly gym membership they never use (and thus subsidizing it for the rest of us).

“I AM GOING TO JAPAN SOON AND NEED TO LEARN SOME JAPANESE FAST!”

it may be hard to believe now, but japan hasn’t always been a major international tourist destination. as recently as 20 years ago, it was unusually unpopular among tourists for its size, history, economy, etc. part of it was that it had developed a well-deserved reputation for impenetrability due to its insularity, the majority of tourist infrastructure within japan catered only to domestic tourists. back then it was genuinely difficult to get around without hiring guides or joining tour groups, having local friends show you around, or doing extensive research and studying the language before your trip.

things are a lot different since japan has transformed into a cool tourist destination, and many companies in japan are now courting foreign tourists to try and get a slice of the pie in one of the japanese economy’s only growing segments. even though the main drivers of the tourism increase are other asian countries like china, it’s still resulted in significant infrastructure improvements for international tourists in general. what this means is that all the old impressions of japan are outdated and nowadays you can travel to japan as casually as you might visit a long-standing tourist staple like france, not needing to make any special arrangements or knowing anything of the language besides maybe “arigato”. i speak from personal experience: i didn’t know a lick of a japanese when i visited for a month in 2017 and everything went just fine.

as such, i wouldn’t recommend trying too hard to learn much japanese if your sole reason for doing so is because you’re taking a trip there for a week or two, it’s unnecessary and almost certainly not worth the effort. if you’re going to japan soon and want to use an upcoming trip as a catalyst for beginning long-term study of the language, then by all means go ahead, just don’t expect to get anywhere particularly useful unless you put in a ton of hours or your trip is really far in the future. for example, if you’ve got three months before your trip, with four hours of intensive study per day every day before your trip, you might be able to get to borderline conversational.

don’t feel that you have to embark on a brutal course of study before your trip, though. as i’ve said, it’s not necessary for survival over there, so don’t stress over it. i have even heard of some expats who have lived in japan for decades who barely know the language (they usually have a japanese spouse or friends who take care of all the hard government bureacracy stuff). knowing japanese can enhance your experience but not by that much - if by some chance you harbor a dream of chatting up the locals in a neighborhood izakaya or something, that's possible now even without being conversational in the language thanks to how good translation apps have gotten. a guy i follow online has entire conversations with random bar patrons in exotic destinations like mongolia where he doesn’t know the language whatsoever, all through the “conversation” feature on the google translate app.

A WARNING CONCERNING “COMMUNITIES”

the popularity of japanese, especially among the overly-online segment, means that there’s a verdant ecosystem of online “japanese learning communities” out there to join. though i’m sure there’s some personality types that can extract some value or additional motivation from participating in them, be warned: if you really want to learn japanese, don’t let “participating in a japanese learning community” replace “actually learning japanese”. discord's ephemeral mass instant messaging format is especially vulnerable to this effect, without realizing it you might find yourself constantly chatting with others in english about learning japanese instead of actually learning it. before long, discussion topics in the server start drifting away from japanese learning or anything to do with japan at all, the server staff open up the #offtopic channel for those conversations or even worse, the dreaded #politics channel, you start spending all your time in that channel with your fellow community members talking about the latest movies or video games, venting about your relationship woes, reposting news articles and political memes and getting into arguments, eventually forgetting the original purpose of the server and why you joined in the first place. don’t let that be you – nobody’s ever been on their deathbed thinking “damn, i wish i spent more time arguing about politics in the discord for an australian minecraft school roleplay server with a swedish monarchist, a bangladeshi islamic fundamentalist, a diehard sanders stan stoner, a lost normie democrat who adheres to the party line with parodic strictness, a furry tankie, and an anarchist who’s also the server admin, ready with a mute or ban if things get out of control in chat...”

ONE NEAT TRICK

protip: trick yourself into thinking anything you do fully in japanese is productive. watching anime normally: bad! waste of time! watching anime IN JAPANESE: good! language learning! productive!

JESUIT JAPANESE

for those still anxious over choosing the best method to learn japanese, it may be helpful to step back and recall that people back in old timey-times learned japanese using nothing less than janky old j-e/e-j PHYSICAL (the horror!) dictionaries and flashcards made BY HAND. some even implemented a basic manual version of anki's spaced repitition algorithm by sorting flashcards into a couple of boxes. going back way further, the jesuit priests who entered the country in the 16th century started from scratch, no guides or dictionaries or anything. somehow they got things going strong enough that there are still catholics in japan after centuries of repression and even after the two most catholic cities in japan got nuked (do NOT research). what, they had an advantage because they were motivated by a deep religious duty to convert heathens? are you saying that you do not love anime girls nearly as much as 16th century jesuits loved jesus? pathetic.

THE SECRET FORBIDDEN TECHNIQUE

warning: objectionable content

FACT: amidst their enormous cultural output, the japanese also happen to be one of the world’s most prolific producers of pornographic content. maybe you’re already aware of this and the reason you’re learning japanese is for the porn, i don’t know. regardless, anybody with a sex drive can take advantage of this to motivate themselves to read more in japanese. for example, you could allow yourself to read unlimited doujinshi so long as it’s done in japanese, and you must finish reading an entire one before finishing (so to speak). the only downside is that you can only get so far using this particular method because the vocabulary and grammar used in many doujinshi tends to be quite limited.

the REAL killer app for hi-jacking sex drive to learn japanese, though, is visual novels. the majority of them contain sexual content, to the extent that they're referred to in japanese as "eroge". many are structured such that you might almost think that they were made for the express purpose of facilitating sex-motivated japanese learning. they will string you along through hours and hours of reading, drip-feeding increasingly-escalating erotic scenes as a reward for your perseverance. the next sexy scene is just around the corner, you think, and before you know it you've done another 8 hours of japanese reading in your lust.

the amount of reading required to reach erotic scenes in certain visual novels approaches truly outrageous heights sometimeswhy are so many vns so fucking long? simple, it is because they are essentially a sophisticated new form of pornography: “relationship porn”. to simulate a relationship they require a significant time investment and plenty of non-sexual, quotidian relationship content like “hanging out and talking”. , many real-life girls put out far quicker than vn girls. in some vns there might be 20 hours of reading before you're teased with a beach scene, then another 10 hours in, maybe the player character accidentally walks in on the girl dressing and you finally see a nipple. 10 hours later, a kiss, and finally, you're so close, you're reading reams of insipid slice-of-life dialogue in japanese at a fevered pace and can't tear yourself away because you're so close to the big pay off, finally going all the way... before you know it you've managed 50 hours of reading/listening in japanese all for the promise of some pixelated pussy and high-pitched voice actress moaning (i always wonder what it must be like to be in the studio when some of that stuff is recorded). people learning something like spanish don't have access to such fearsome tools.